Switched systems are a class of dynamic systems in which the vector field defining the dynamics changes at discrete time instants. For example, an electrical system with a electrical switch is a switched system as the behavior of the current flow will change with the flicking of the switch. Additionally, a person walking is a switched system since the foot’s motion switches when it contacts the ground. In controls, a feedback loop that switches feedback gains is a switched system.

The goal of this project is to develop systematic procedures to choose the optimal switching behavior. As is often the case for optimal control nonlinear systems, I turn to iterative methods. These methods often have the form:

- make an initial guess of the switching behavior,

- pick a descending direction from current switching behavior,

- pick a size to step in that direction,

- update switching behavior,

- repeat from 2. until satisfied.

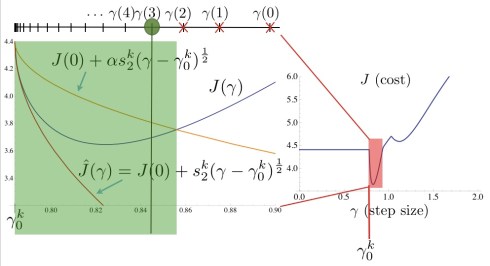

Those familiar with iterative optimization should be familiar with this type of algorithm. The difficulty lies in doing steps 2. and 3. correctly so that after enough iteration evaluations, the algorithm has converged to within some acceptable error. Often, step 2. is chosen from derivative information like gradients and Hessians, except, we will find that for switched systems, they do not always exist (this is because the space of switched system control inputs is infinite dimensional and does not form a Hilbert space). For step 3, I turn to an Armijo-like line search with backtracking. This sort of line search is shown in the above figure and is fundamental to designing a convergent switched system optimization algorithm.

The switched system optimization problem comes in two flavors. The first assumes a sequence of switching behaviors is set and the timing of the switches are the design variables. I refer to this problem as switching time optimization. The second does not make such an assumption and optimizes over the sequence and timings together. I put emphasis on “together,” as one strategy would be to optimize the switching times for any reasonable sequence, but this would lead to a combinatoric explosion. I instead use a projection-based method which scales well with the number of states. I refer to this problem as mode scheduling.

This project has three main components:

- hybrid sensitivity

- switching time optimization, and

- mode scheduling.

Please see the following videos for more information.

Relevant Videos:

A simple, yet enlightening, switched system example is a pendulum that can switch between two different values of gravity. This is a non-physical example, but could be approximated using a motor at the base of the pendulum. The pendulum’s two possible modes are shown below. I use orange and blue to distinguish which mode the pendulum is currently in.

| Pendulum swinging with lesser gravity in the “orange” mode. A full swing takes about 5 seconds. | Pendulum swinging with greater gravity in the “blue”mode. A full swing takes about 7 seconds. |

We look at two goals. The first is to calculate the switching behavior that most “stabilizes” the pendulum (left video). The second is the opposite: to calculate the switching behavior which most “destabilizes” the pendulum (right video). Both of the solutions shown below were systematically calculated using mode scheduling with an initial guess of no switches.

| Simulation of the pendulum swinging with the most “stabilizing” switching behavior. Notice that mode scheduling automatically finds the solution to switch to the heavier gravity for upswings and the lesser gravity for downswings. | Simulation of the pendulum swinging with the most “destabilizing” switching behavior. Notice that mode scheduling automatically finds the solution to mostly switch to the heavier gravity for downswings and the lesser gravity for upswings. During the first upswing, though, it finds that a short period of time with the heavier gravity will make the pendulum flip sooner. |

Relevant Papers:

- [1]

- T.M. Caldwell. Iterative methods in switched system optimal control, 2013. (Doctoral Dissertation) [link]

- [2]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Sufficient descent and backtracking for optimal mode scheduling. (Submitted to IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control)

- [3]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Single integration optimization of linear time-varying switched systems, IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 57:1592-1597, 2012. [link]

- [4]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Switching mode generation and optimal estimation with application to skid-steering. Automatica, 47:50-65, 2011. [link]

- [5]

- T.M. Caldwell. Second-order optimal estimation of switching times for switched autonomous systems, 2009. (Master’s Dissertation) [link]

- [6]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Projection-based switched system optimization: Absolute continuity of the line search, Conference on Decision and Control, p700-706, 2012. [link]

- [7]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Projection-based switched system optimization, American Control Conference, 2012. p4552-4557, 2012. [link]

- [8]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Single integration optimization of linear time-varying switched systems, American Control Conference, p2024-2030, 2011. [link]

- [9]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. An adjoint method for second-order switching time optimization, Conference on Decision and Control, p2155-2162, 2010. [link]

- [10]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Relaxed optimization for mode estimation in skid-steering, IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, p5423 – 5428, 2010. [link]

- [11]

- T.M. Caldwell and T.D. Murphey. Second-order optimal estimation of slip state for a simple slip-steered vehicle, IEEE Conference on Automation Science and Engineering, p133-139, 2009. [link]